What happened in the Velvet Revolution?

Topic of Study [For H2 and H1 History Students]:

Paper 1: Understanding the Cold War (1945-1991)

Section A: Source-based Case Study

Theme I Chapter 3: End of Bipolarity

Historical context: Commemorating the International Students’ Day

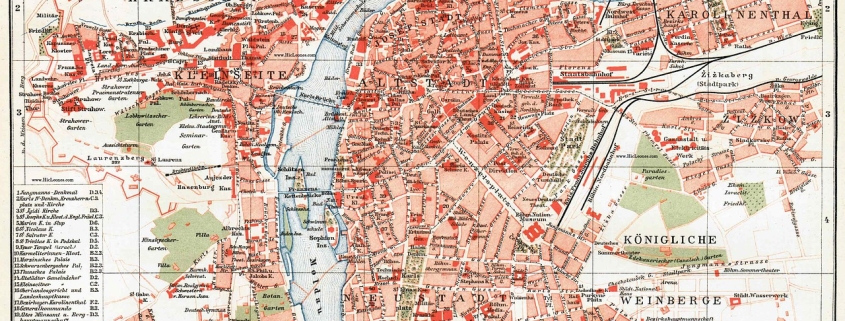

On 17 November 1989, student demonstrations were held in Prague, marking the 50th anniversary of International Students’ Day. On the very same day in 1939, a Nazi attack was launched on the Prague University, leading to the deaths of nine students and detainment of 1,200 students. After the end of the Second World War, a pro-Communist government was formed in Czechoslovakia, which suppressed dissent. Yet, the government sanction the celebration of the International Students’ Day.

November 17, 1989, was the fiftieth anniversary of the death of Jan Opletal, a date with special historical significance in Bohemia and Moravia. On this day in 1939, Adolf Hitler, angered by Czech resistance to the German occupation of rump Czechoslovakia, unleashed his Special Action Prague, during which nine student leaders were executed and a further 1,200 university students transported to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

An excerpt from “The Velvet Revolution: Czechoslovakia, 1988-1991” by Bernard Wheaton and Zdeněk Kavan.

Dubček‘s Prague Spring

Before the Velvet Revolution, the Czech people had made a failed attempt to resist Soviet control in the 1960s. In January 1968, Alexander Dubček was made leader of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Contrary to expectations, Dubček introduced political and economic reforms, including the freedom of speech and freedom of the press. His reforms had given rise to the Prague Spring. Yet, Moscow opposed this change, seeing a liberal Czechoslovakia as a threat to its regional power.

In August 1968, half a million Warsaw Pact troops invaded Czechoslovakia, suppressing student-led protests. Dubček was replaced by a loyalist Gustav Husak and reverted the country to authoritarian rule. Nevertheless, the Prague Spring had left a lasting impression on the people at the international level.

For once, the Communist and non-Communist worlds — and some countries that find themselves in between — joined in a general condemnation of Soviet force. The free world is accustomed to condemning Russian inroads and intransigence, from the brutal putdown of the Hungarian revolt to the erection of the Berlin Wall. In the past, most Communist countries and parties have either wholeheartedly supported such transgressions—or at least closed their eyes to them—but no longer. Last week, in one country after another, Communists found themselves on the side of the Czechoslovaks.

An excerpt from a Time newspaper article titled “World: The Reaction: Dismay and Disgust” on 30 August 1968.

Defeating the Great Evil

Notably, the 1989 demonstrations took place eight days after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Even in the face of violent threats by the police, the Czechs persisted. By 20 November, half a million Czechs and Slovaks occupied the Wenceslas Square of Prague, chanting anti-government slogans.

On November 26, 1989, three-quarters of a million people congregated in Prague, followed the next day by a two-hour nationwide strike. The Federal Assembly discarded constitutional provisions guaranteeing the Communist Party’s preeminent role, along with Marxism-Leninism as the official state ideology. New Communist Party leaders struggled to retain power, promising on December 3 to allow for fuller representation, genuine elections, protection of civil liberties, and removal of political pressures in places of employment. None of that sufficed, and on December 7, after 25,000 party members had resigned, Prime Minister Ladislav Adamec did as well. Three days later, the Communist government fell, with Husak resigning and a Government of National Understanding established.

An excerpt from “The Czech Republic: The Velvet Revolution” by Robert C. Cottrell.

Eventually, popular movements have successfully defeated the Communism. On 28 November, the Communist Party resigned, allowing an anti-Communist government to take over. A key dissident and writer, Václav Havel, was elected president a month later.

The worst thing is that we live in a contaminated moral environment. We fell morally ill because we got used to saying something different from what we thought. We learned not to believe in anything, to ignore each other, to care only for ourselves. Concepts such as love, friendship, compassion, humility, and forgiveness lost their depth and dimensions… . The previous regime… . reduced man to a force of production and nature to a tool of production… . It reduced gifted an autonomous people to nuts and bolts in some monstrously huge, noisy, and stinking machine, whose real purpose was not clear to anyone …

An excerpt from the speech titled “New Year’s Address to the Nation” by Czech President Václav Havel, 1 January 1990.

What can we learn from this article?

Consider the following question:

– How far do you agree that People Power was the main cause for the end of Bipolarity in the 1980s?

Join our JC History Tuition to learn more about the End of Bipolarity. The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.