When did Indonesia get West Papua?

Topic of Study [For H2 History Students]:

Paper 2: Regional Conflicts and Co-operation

Source Based Case Study

Theme III Chapter 1: Inter-state tensions and co-operation: Causes of inter-state tensions

Historical background: The West New Guinea dispute

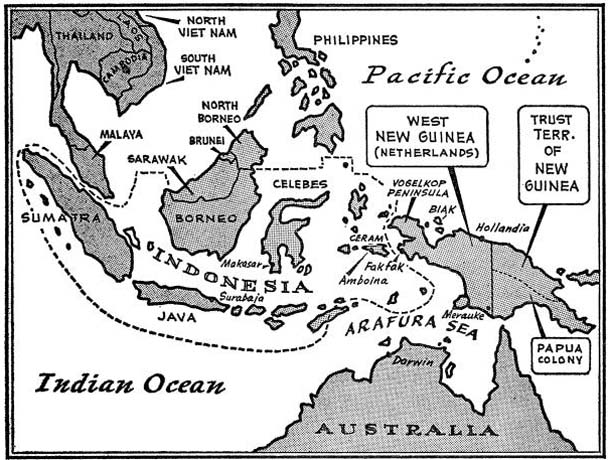

After the Netherlands ceded sovereignty to Indonesia on 27 December 1949, the Dutch retained control over the Western part of New Guinea (also known as ‘West Irian’). Its native inhabitants, the Papuans, have occupied the land for over 40,000 years.

More importantly, the Dutch continued to occupy West New Guinea for strategic reasons. The Netherlands can not only capitalise on the resource-rich territory, but also maintain its regional presence in Southeast Asia. In contrast, Sukarno believed that Indonesia should take control of West New Guinea to complete the decolonisation process.

According to the Netherlands, the 700,000 inhabitants of West Irian were racially and culturally unrelated to the Indonesians. Indonesia’s position was that its nationalist project had a territorial, rather than a racial, basis and was rooted in common suffering endured during the Dutch colonial occupation.

An excerpt taken from “Self-Determination in Disputed Colonial Territories” by Jamie Trinidad.

International responses

In 1954, Indonesia raised its concerns of West New Guinea in the 9th Session of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). Then, Sukarno garnered support from the Afro-Asian nations during the Bandung Conference in April 1955.

International opinion on the matter was divided. While Indonesia had the backing of the Afro-Asian nations, the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies, the Netherlands was supported by Latin American nations and other key Western powers like the USA and the UK. Notably, Australia opposed Indonesia’s claim of West New Guinea, citing security concerns as the former administered the eastern part of the disputed territory.

There were, of course, no immediate direct results to be anticipated from this but it served notice on the world that the Indonesian struggle for West Irian now officially had behind it the support of virtually all the independent and semi-independent nations of Asia – including Communist China – and Africa, the populations of which comprised the vast majority of mankind.

An excerpt taken from “The Dynamics of the Western New Guinea Problem” by Robert C. Bone.

By 1960, more nations supported the aim to put an end to the West New Guinea dispute. On 27 November 1961, the UNGA failed to pass a resolution on the dispute as some member nations favoured the resumption of Dutch-Indonesian talks while others preferred an independent West New Guinea. Consequently, Sukarno was certain that a military campaign was necessary to wrestle control from the Dutch.

Operation Trikora & New York Agreement

On 19 December 1961, Sukarno ordered the Indonesian military to commence a full-scale invasion of West New Guinea. In response, the Dutch ramped up its military presence. Fortunately, the military operation ended when the both parties agreed to sign the New York Agreement on 15 August 1962. Under General Assembly Resolution 1752 (XVII), the United Nations would administer West New Guinea temporarily before the territory is handed over to Indonesia.

The stand-off between the Netherlands and its former colony resulted in a crisis in December of 1961 when Indonesian President Sukarno prepared for and threatened armed conflict. An agreement was negotiated under the supervision of the UN as a result of strong political pressure from the USA. […] The New York Agreement provided for a UN-supervised popular consultation in order to give the Papuans the freedom of choice in determining their future.

An excerpt taken from “Peacebuilding and International Administration: The Cases of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo” by Niels van Willigen.

What can we learn from this article?

Consider the following question:

– Assess the view that the Indonesian Confrontation broke out due to ideological differences.

Join our JC History Tuition to learn more about Inter-state Tensions. The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.