What was the Tet Offensive?

Topic of Study [For H2 History Students]:

Paper 1: Understanding the Cold War (1945-1991)

Section A: Source-based Case Study

Theme I Chapter 2: A World Divided by the Cold War – Manifestations of the global Cold War: Vietnam War (1959-75)

Topic of Study [For H1 History Students]:

Essay Questions

Theme III Chapter 1: The Cold War and Southeast Asia (1945-1991): Factors shaping the Second Indochina War (1959–1975)

Historical Context: Ho Chi Minh’s Plan

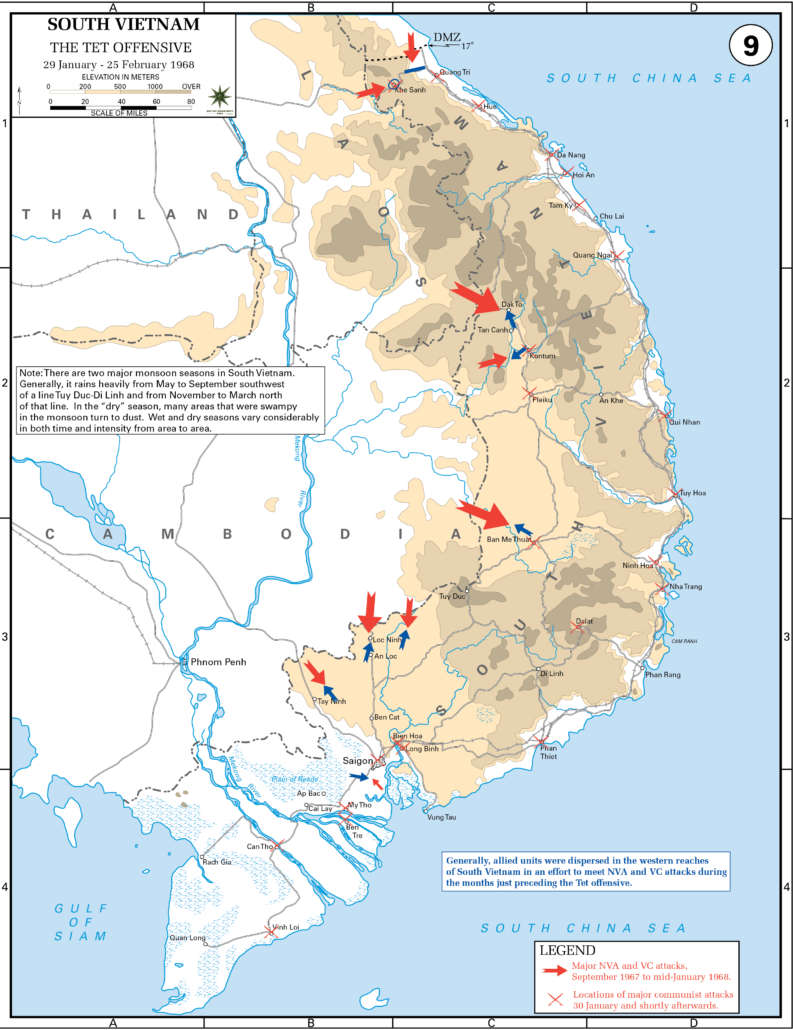

On 30-31 January 1968, the North Vietnamese forces and the Viet Cong launched a coordinated military campaign in South Vietnam. It coincided with the Vietnamese New Year, known as the Tet, in which many South Vietnamese soldiers were preoccupied with this celebration.

Ho Chi Minh formulated this plan to carry out the Tet Offensive to achieve two main goals:

- To sow discord between the United States and South Vietnamese forces.

- To cause an internal collapse of authority within South Vietnam and spark unrest to oppose the Saigon regime.

During the Battle of Hue, the Viet Cong overran the city and took control of Hue, claiming the lives of thousands of inhabitants within. The Allied troops had to take nearly a month to regain control of Hue. In doing so, the USA had incurred rising casualties, which was a problem concealed by the government.

The Viet Cong fighters piled into a truck and a taxicab and drove to their target. Just before 3 A.M., as they drove past the night gate, the Viet Cong opened fire on the two American guards stationed there. […] Shortly after 9 A.M., the embassy was officially declared clear of all enemy fighters. General William Westmoreland, commander of all U.S. forces in Vietnam, strode onto the embassy grounds in clean, pressed uniform. Westmoreland told reporters that the attack on the embassy had been part of a wider Viet Cong assault across Vietnam. He complained that the Viet Cong had broken a holiday truce to stage these attacks.

An excerpt taken from “The Tet Offensive: Turning Point of the Vietnam War” by Dale Anderson.

Although the campaign targeted more than 100 cities and towns, including the southern capital Saigon, it was a catastrophic military disaster for the communists. As many as 50,000 communist troops died in their attempt to gain control of South Vietnam.

Illustration provided by West Point, US Military Academy.

Unintended Consequences: The Quagmire

Nonetheless, the repercussions of the Tet Offensive on the United States were serious. As the Johnson administration had repeatedly reassured the American public that a swift and decisive victory was possible in Vietnam, the Tet Offensive had raised doubts on this promise.

The American journalist Walter Cronkite had exposed the deception of the Johnson administration in a provoking broadcast. This revelation was made after his personal trip to Hue in Vietnam, in which the most intense urban warfare took place during the war.

We have been too often disappointed by the optimism of the American leaders, both in Vietnam and Washington, to have faith any longer in the silver linings they find in the darkest clouds. […]

To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past. To suggest we are on the edge of defeat is to yield to unreasonable pessimism. To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion. On the off chance that military and political analysts are right, in the next few months we must test the enemy’s intentions, in case this is indeed his last big gasp before negotiations. But it is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could.

An excerpt taken from Walter Cronkite’s “We are mired in stalemate” broadcast, 27 February 1968.

As a result, public sentiments became to shift in favour of US withdrawal from Vietnam, given that the people realised that a victory in Vietnam was unlikely, as outlined by Cronkite’s broadcast. Faced with mounting popular pressure, Johnson announced on 31 March 1968 that he would not seek a second term as president of the United States. His successor, Richard Nixon, then proceed with the policy of “Vietnamisation“, which led to a new phase of the US role in the Second Indochina War.

Join our JC History Tuition to learn more about the Vietnam War, Korean War and Cuban Missile Crisis. The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.