When was ASEAN formed?

Topic of Study [For H2 History Students]:

Paper 2: Regional Conflicts and Co-operation

Source Based Case Study

Theme III Chapter 1: Reasons for the formation of ASEAN

Topic of Study [For H1 History Students]:

Essay Questions

Theme II Chapter 2: The Cold War and Southeast Asia (1945-1991): ASEAN and the Cold War (ASEAN’s responses to Cold War bipolarity)

Historical context: Konfrontasi, an undeclared war

Before the founding of ASEAN, Southeast Asia was affected by conflicts that broke out due to political differences among neigbouring countries. Furthermore, the Cold War rivalry had expanded into the region, pressuring governments to take a side.

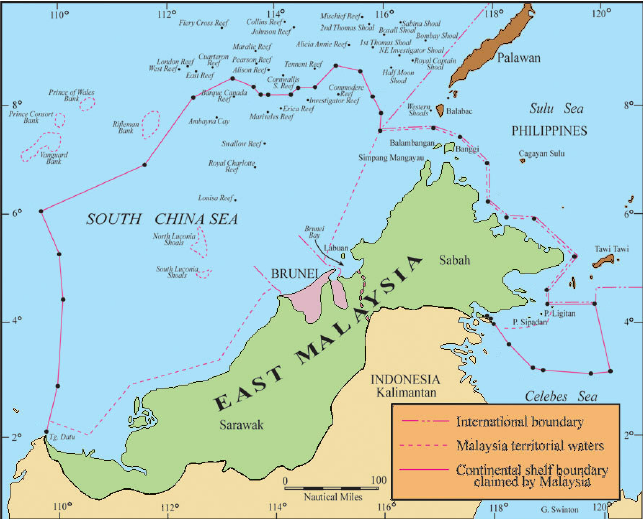

In particular, the Indonesian leader Sukarno expressed disapproval at the formation of the Malaysian Federation in 1963, which sparked a three-year conflict. Philippines also disputed the creation of the Federation due to the inclusion of Sabah.

Following the rise of Suharto, the Indonesian government expressed desire to mend diplomatic ties with Malaysia, as evidenced by the official end of the Confrontation in August 1966. As a leader that desired regional leadership, Suharto supported the formation of ASEAN as a regional organisation to unite neighbouring countries.

ASEAN was born in the aftermath of the tense and and destabilising Konfrontasi (Confrontation) of 1963-1966, which President Sukarno of Indonesia had launched against the Federation of Malaysia to protest its formation. Thanat Khoman – Foreign Minister of Thailand from 1959 to 1971 – was attempting to broker a reconciliation between Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia that he broached the idea of forming a new organisation for regional cooperation to Indonesian Foreign Minister Adam Malik, and on 8 August 1967, the five foreign ministers of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand came together in the main hall of the Thai Foreign Affairs Department to sign what is now known as the ASEAN Declaration or Bangkok Declaration.

An excerpt from “ASEAN Law and Regional Integration: Governance and the Rule of Law in Southeast Asia’s Single Market” by Diane A Desierto and David J Cohen.

Functions of ASEAN

Following the creation of ASEAN in August 1967, the regional organisation had developed four main methods of cooperation: the non-use of force, pacific settlement of disputes, regional autonomy and non-interference. Member nations have agreed to forge regional cooperation through diplomatic means, while avoiding the use of military force.

The establishment of ASEAN was the product of a desire by its five original members to create a mechanism for war prevention and conflict management. The need for such a mechanism was made salient by the fact that ASEAN’s predecessor had foundered on the reefs of intra-regional mistrust and animosity.

An excerpt from “Constructing a Security Community in Southeast Asia: ASEAN and the Problem of Regional Order” by Amitav Acharya.

It was known that its norms were developed as a result of past setbacks, such as the failure of organisations like the Association of Southeast Asia (ASA) and MAPHILINDO. (A grouping that involved Malaysia, the Philippines and Indonesia).

ASEAN Way: Guiding principle for co-operation

The “ASEAN Way” was one of the fundamental features of the regional organisation. It was inspired by Malay cultural practices known as musjawarah and mufukat. In principle, ASEAN functioned on the basis of consensus and consultation.

Antolik identifies three key principles of ASEAN that all member states must adhere to in order to ensure the success of the organization. These are restraint, respect, and responsibility. Restraint refers to a commitment to noninterference in other states’ internal affairs; respect between states is indicated by frequent consultation; and responsibility involves the consideration of each member’s interests and concerns. In practice, ASEAN’s unified policies reflect a consensus that is usually the lowest common denominator among member states… ASEAN is a convergence of the interests of its members.

An excerpt from “Explaining ASEAN: Regionalism in Southeast Asia” by Shaun Narine.

What can we learn from this article?

Consider the following question:

– Assess the political effectiveness of ASEAN in promoting regional unity from 1967 to 1991.

Join our JC History Tuition and learn more ASEAN and other regional and international organisations. The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.