What is the Instrument of Accession?

Topic of Study [For H2 History 9174 Students]:

Paper 1: Conflict and Cooperation (1948-2000)

Section B: Essay Writing

Theme III Chapter 2: Indo-Pakistani Conflict (1947-1972)

Historical context: India divided and the British departure

In 1946, Britain declared that it would grant India independence. The Governor-General Lord Louis Mountbatten declared that this important phase would commence on 15 August 1947. However, views on the ground were divided on the matter.

Leaders of the Indian National Congress Party, Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi, called for a single federal dominion of independent India. They believed that a united India was vital to bring people from all faiths together.

In contrast, the Muslim League leader Muhammad Ali Jinnah insisted that the Partition was necessary to form an independent Pakistan that governs the Muslims rather than to remain subordinate to the Hindu majority of India.

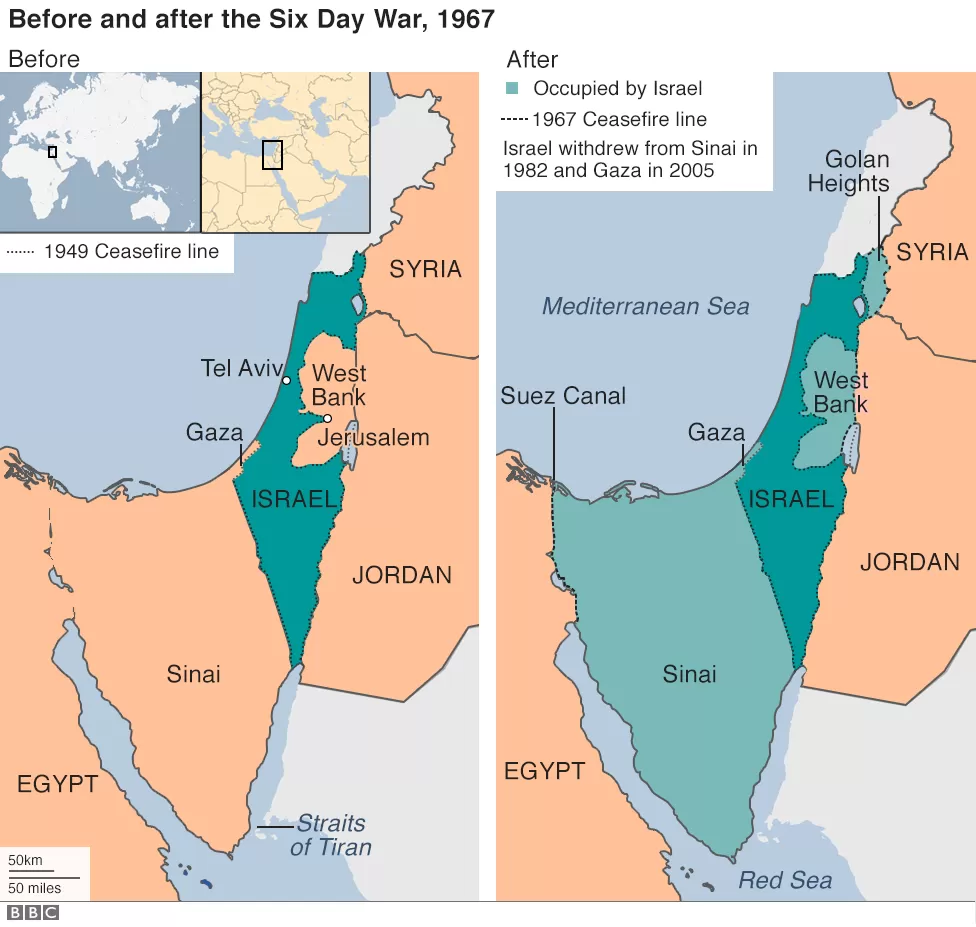

As such, the British civil servant Sir Cyril Radcliffe was tasked by Mountbatten to draw up the borders between India and Pakistan.

In less than ten weeks, a British layers, Cyril Radcliffe, who had never set foot on Indian soil, presided over the partition of British India’s two largest multicultural provinces, Punjab and Bengal.

After first rushing Radcliffe to finish drawing the new maps in desperate haste, Mountbatten embargoed them as soon as Radcliffe finished, refusing to allow even his own British governors of Punjab and Bengal to see where the new lines would be drawn, such that no troops could be stationed at key danger points along these incendiary provincial borders, no warnings could be posted for desperate people who, overnight, found themselves living in ‘enemy’ countries rather than among relatives and friends.

An excerpt taken from “India and Pakistan: Continued Conflict or Cooperation?” by Stanley Wolpert.

As a result of the Partition, many Hindus and Muslims were subjected to violent attacks from opposing sides. An estimated of up to 20 million people were displaced as a result of the Partition.

Enter Maharaja Hari Singh: Jammu and Kashmir

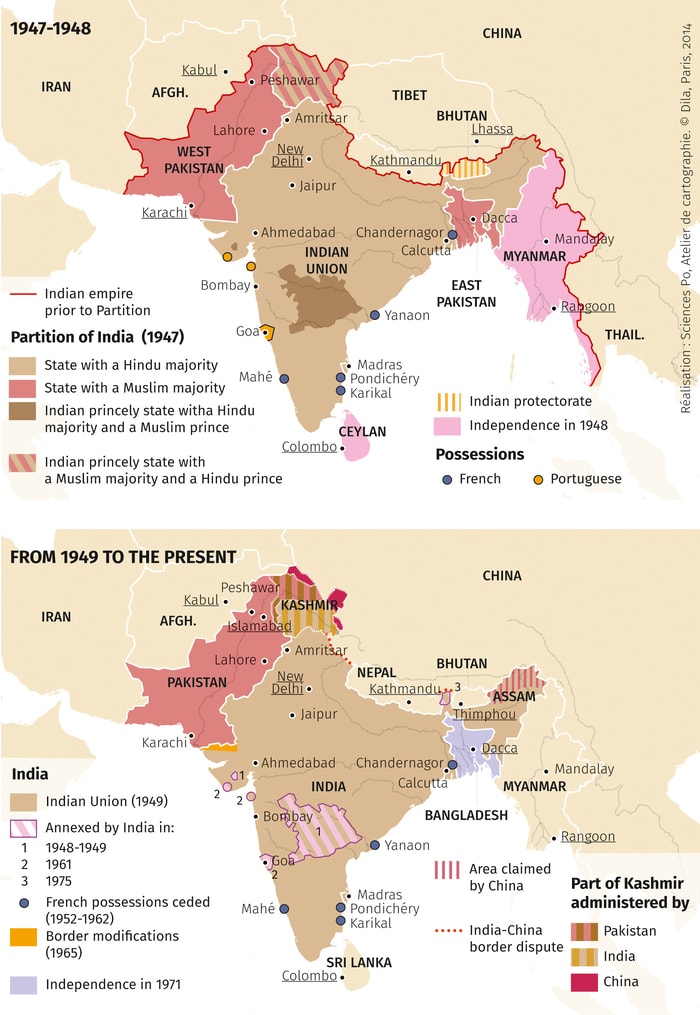

On 26 October 1947, Maharaja Hari Singh, then ruler of the State of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), signed the Instrument of Accession (IoA) with India. Initially, Hari Singh wanted Kashmir to remain independent, but changed his mind when attacked by tribesmen from Pakistan during the Poonch uprising.

J&K was founded by Maharaja Gulab Singh in 1846. It was strategically located within the border provinces of Gilgit-Baltistan and Ladakh, thus explaining it being a hotly contested territory.

The circumstances, as they developed owing to the raids of tribesmen, were such that immediate action was uncalled for. The invasion of tribesmen was possible only because of Pakistani support. Mahajan commented: “The tribesmen were subjects of Pakistan. This was an unprovoked act of aggression. The Maharaja had done nothing to invite it. […] Unless accession took place and supported by the National Conference, Nehru was unwilling to send Indian army.

An excerpt from “Jammu and Kashmir: The Cold War and The West” by D. N. Panigrahi.

On that same day, Mountbatten accepted the accession of J&K.

Join our JC History Tuition to learn more about the Indo-Pakistani conflict under the theme of Conflict and Cooperation. The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.