What was the main objective of the Baruch Plan?

T

Topic of Study [For H2 and H1 History Students]:

Paper 1: Understanding the Cold War (1945-1991)

Section A: Source-based Case Study

Theme I Chapter 1: Emergence of Bipolarity after the Second World War II

“Before a country is ready to relinquish any winning weapons, it must have more than words to reassure it.”

Bernard M. Baruch, June 1946.

Historical context

In August 1945, the United States dropped two atomic bombs, ‘Little Boy’ and ‘Fat Man’, on Japan. As a result of their destructive capabilities, Japan surrendered, securing an American victory that ended the Second World War (WWII).

Afterwards, the Truman administration held a discussion, contemplating on the sharing of atomic secrets with the Soviet Union. The meeting was attended by notable officials, like Secretary of War Henry Stimson and State Department official George Kennan. The general consensus was that the end of US atomic monopoly may erode Russian suspicions and avert an arms race. Interestingly, Kennan opposed the notion of revealing their trump card to the Soviet Union, claiming that the Soviets could not be trusted.

In 1945 and the succeeding several years three broad policy options were available to the United States government. First, it could actively strive to reach an agreement with other countries for the international control of nuclear energy. […] A second option opposed this position. It emphasized the advantages that could be attained from exclusive American control of the new technology. […] The third and final broad option took shape only towards the end of the 1940s, after the harsh antagonisms of the Cold War had imposed their icy grip on international relations. This option proposed a preventive nuclear strike against the Soviet Union.

An excerpt from “Nuclear Fallacies: How We Have Been Misguided since Hiroshima” by Robert W. Malcolmson.

Enter Bernard Baruch

In early 1946, the USA proposed the establishment of the United Nations Atomic Energy Commission (UNAEC). ITs role was to control the development and proliferation of nuclear weapons and technology. An advisor to US Presidents, Bernard Mannes Baruch, present proposal to the United Nations.

When Baruch made the proposal on 14 June 1946, he included the need for international control and inspection of nuclear production facilities. Baruch’s proposal was based on the Acheson-Lilienthal report, which sought control of all activities deemed dangerous to global security.

Yet, he made a clear point that the USA would keep its monopoly over nuclear weapons until the proposal was put into action. Although Baruch claimed that it was the ‘last, best hope of earth’, the Soviet Union objected, offering a counterproposal to ban all nuclear weapons. It was not surprising that the USA rejected the Soviet Union’s suggestion.

By summer, it had become hopeless. The distinguished Chicago sociologist Edward Shils lamented the new status quo: “At present the situation is so unpromising as far as atomic energy control as such is concerned that even if the Soviets were to accept the majority plan, the American people and their leaders might indeed be too distrustful of the Soviets to accept their scheme which they themselves had proposed.” In June, the majority (supporters of a modified Baruch Plan) and the Soviet Union had hardened their stances to a deadlock, and in the fall of 1948 the UNAEC referred the issue to the General Assembly. It would bounce around for another year, only to die quietly in November 1949 after Soviet proliferation rendered the issue moot.

An excerpt taken from “Red Cloud at Dawn: Truman, Stalin, and the End of the Atomic Monopoly” by Michael D. Gordin.

The Soviet Union asserted that the USA could use its atomic monopoly to coerce other nations into accepting its plan. Eventually, the Plan fizzled out. The USA insisted on retaining its monopoly as a deterrent against the Soviet troops amassed in Eastern Europe.

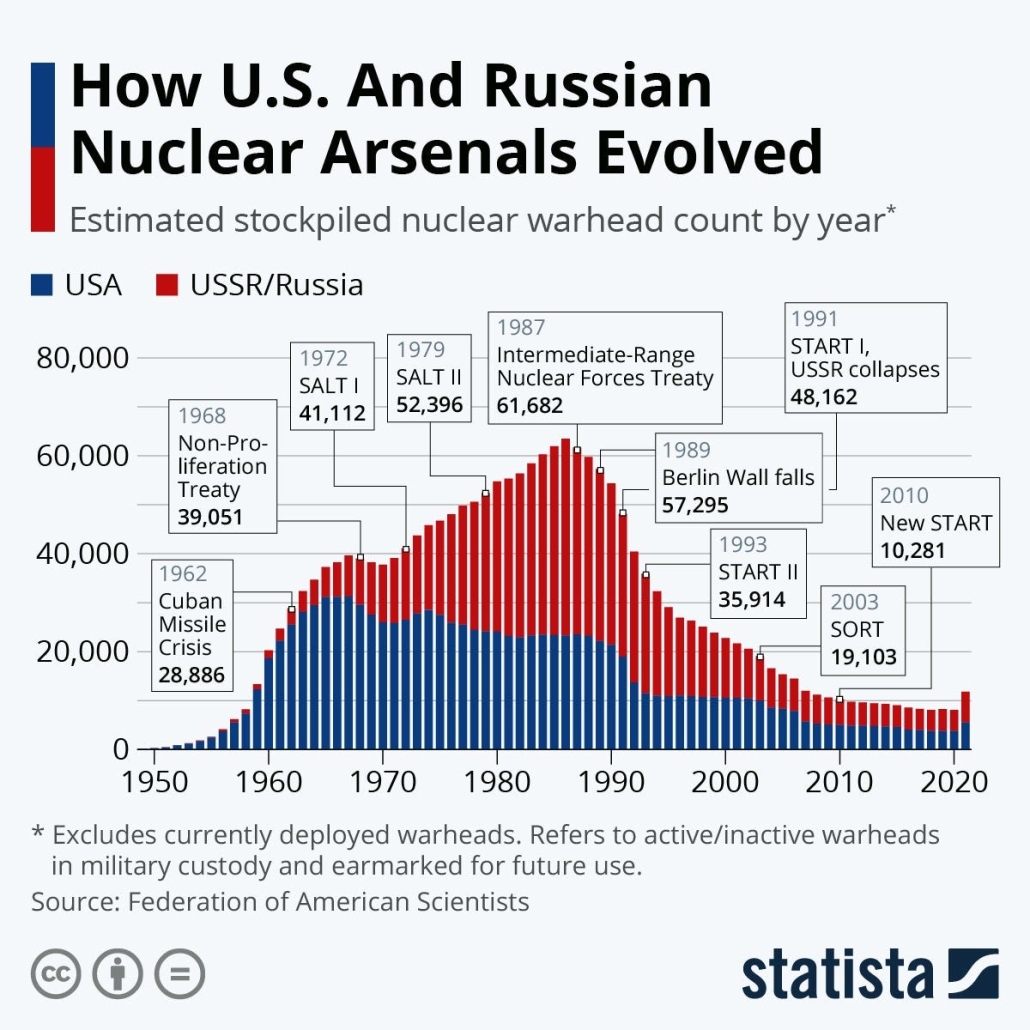

Arms Race

By 1949, the notion of arms control was a lofty one. In September 1949, the Soviet Union tested a nuclear device successfully, ending the US atomic monopoly.

As the shock of the Russian bomb wore off, the Truman administration seemed outwardly unaffected by the atomic monopoly’s end. The President’s own repeated public assurances that the Soviet test had not taken the United States unawares even seemed an implicit argument against any steps to counter the Russians’ achievement. But Truman’s claim that the government had not been surprised was freely contradicted by a consensus of newspaper and magazine articles following announcement of the test.

An excerpt taken from “The Winning Weapon: The Atomic Bomb in the Cold War, 1945-1950” by Gregg Herken.

What can we learn from this article?

Consider the following question:

– Assess the view that the failed Baruch Plan contributed to the start of the nuclear arms race in the late 1940s.

Join our JC History Tuition to learn more about the Cold War. The H2 and H1 History Tuition feature online discussion and writing practices to enhance your knowledge application skills. Get useful study notes and clarify your doubts on the subject with the tutor. You can also follow our Telegram Channel to get useful updates.

We have other JC tuition classes, such as JC Math Tuition and JC Chemistry Tuition. For Secondary Tuition, we provide Secondary English Tuition, Secondary Math tuition, Secondary Chemistry Tuition, Social Studies Tuition, Geography, History Tuition and Secondary Economics Tuition. For Primary Tuition, we have Primary English, Math and Science Tuition. Call 9658 5789 to find out more.